We are both playing with coins, so why do you consider it an "illegal operation"?

1. Regulatory Signals Behind the Escalation of Jurisdiction in a Sichuan Virtual Currency Case

In the Supreme People’s Court’s 2024 Model Cases of Escalated Jurisdiction, released on July 29, 2025, Case 200—concerning Wu Mouyuan and others convicted of illegal business operations—stands out as both a precedent and a guide for future cases. The matter was initially heard by the Muchuan County People’s Court in Sichuan. The court determined the case involved the legal classification of foreign exchange transactions mediated by virtual currency. Given regional disparities in the understanding of virtual currency legality and ongoing debates over the legal nature of such conduct, the case was submitted to the Leshan Intermediate People’s Court in Sichuan for escalated jurisdiction.

Attorney Pang Meimei’s research shows that since 2023, more than 30% of criminal cases involving virtual currency and foreign exchange have been handled through escalated or designated jurisdiction. This signals that such cases are now a major focus for judicial authorities as an emerging form of financial crime, and courts are using these cases to set clear adjudication guidelines. Where virtual currencies are deliberately used to evade national foreign exchange controls, courts are committed to uncovering the true nature behind virtual asset transactions—lifting the “veil” and imposing severe penalties for foreign exchange violations. In this particular case, the court found that Wu Mouyuan and associates conducted forex trades via a “RMB–USDT–USD” pathway, sentencing the main perpetrator to 13 years and 6 months in prison for illegal business operations.

2. Legal Analysis: Why Does Using USDT for Currency Exchange Constitute Illegal Business Operations?

Some may ask, “I’ve helped friends exchange currencies—how is that illegal business?”

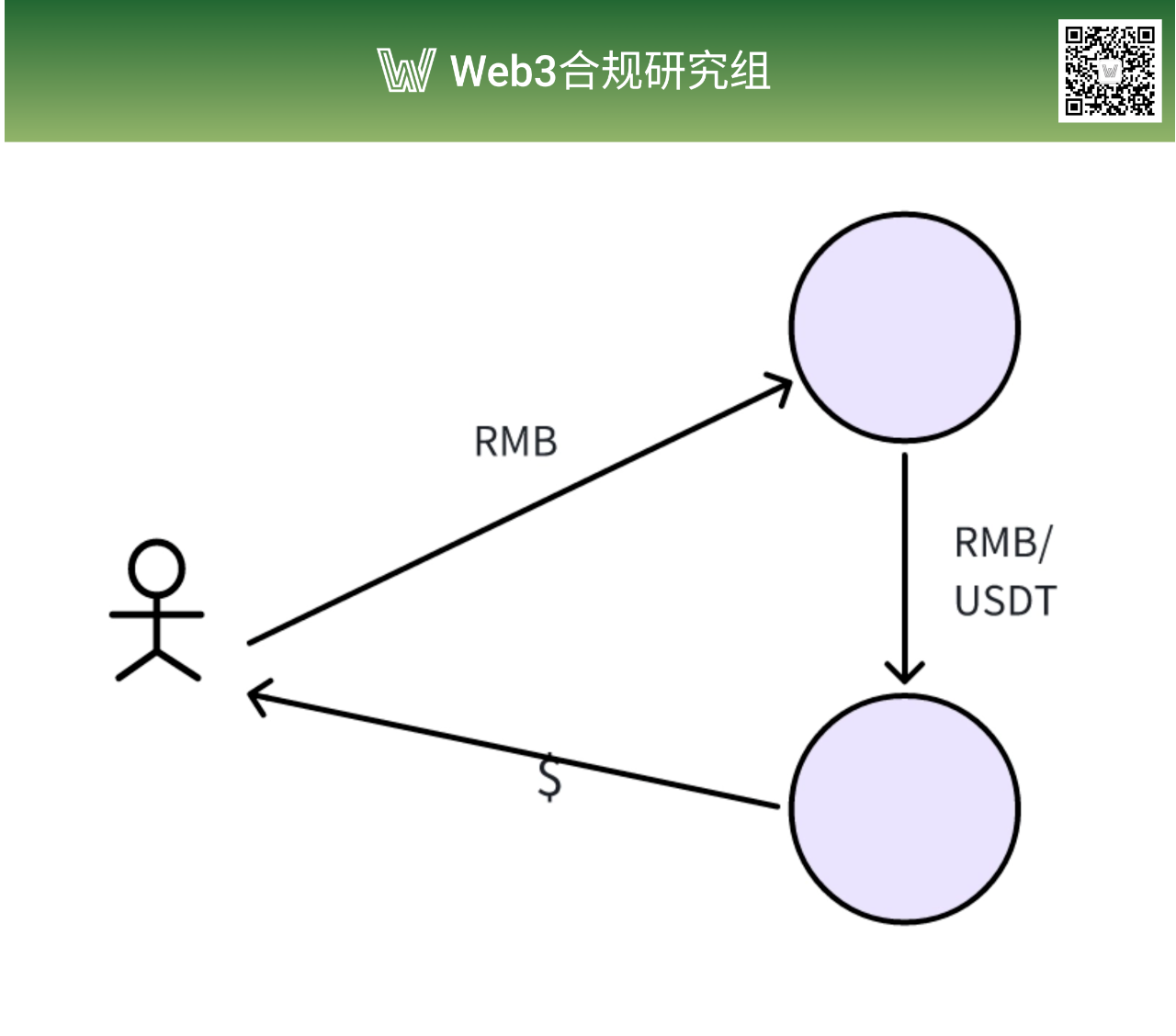

The answer lies in the modus operandi: The Wu Mouyuan syndicate’s core model involved domestic clients transferring RMB to designated accounts. The group would then exchange the equivalent amount into USDT abroad, convert that to USD, and finally credit the USD to the client’s overseas account. This forms a three-link chain: “domestic RMB – overseas USDT – target currency,” with USDT functioning as the “currency converter.”

The Supreme People’s Procuratorate’s 2023 model case specifically pointed out that using virtual currency as an intermediary to swap RMB and foreign currency essentially amounts to illegal forex trading to circumvent regulatory oversight. Even without direct contact with foreign cash, such activity can constitute a crime. In practice, it’s known as a “matched exchange” or “round-trip” transaction: in effect, it forms a closed loop of “RMB in, USD out.”

The principal in this case received 13 years and 6 months—a notably severe sentence for such offenses. In practice, illegal currency exchanges facilitated through crypto often carry stiffer penalties than those conducted via traditional underground banks. Beyond statutory sentencing standards, courts weigh the covert and harmful nature of the methods. Because virtual currency is inherently anonymous, convenient, and cross-border, tracing funds is much harder and the perceived danger of crypto-related crimes is magnified—leading to harsher sentencing.

3. Key Forms of Criminal Activity Involving Virtual Currency

The decentralized and anonymous features of virtual currencies have fueled the growth of the digital economy but, in recent years, have also made them a “natural safe haven” for illicit activity. Attorney Pang Meimei categorizes crypto-related crimes as follows, based on the role virtual asset plays in each case:

Crimes targeting virtual currency itself: Here, the virtual asset is the direct object. The core aim is illegal possession, essentially mirroring traditional theft or robbery—just with the asset shifting from tangible to digital. Classic charges include robbery, theft, and illicit acquisition of computer system data. For example, in case (2021) Hu 02 Criminal Final No. 197, the defendant used technical means to alter a recipient’s account and contact information, successfully transferring another’s Bitcoin to their own control and cashing out. This satisfies the elements of theft—illegal appropriation for personal gain—and the data manipulation also violated computer data laws. Ultimately, the court opted for a theft conviction, reflecting the judiciary’s consensus that virtual currency is indeed property.

Crimes using virtual currency as a tool or medium: Here, crypto is not the goal but the means, used to transfer funds undetected. Its untraceable qualities make it a linchpin in criminal operations, such as gambling, laundering, or providing criminal assistance. In illicit gambling, for example, cross-border casinos require domestic bettors to convert wagers to crypto, sending funds to designated wallets. The anonymity severs links, and suspects launder proceeds using mixing services or cross-chain transfers. In these cases, authorities treat virtual currency as either an equivalent exchange medium or settlement tool.

Crimes based on the “concept” of virtual currency: These are often elaborate scams disguised as innovative investments. Perpetrators proclaim the virtues of blockchain or the appreciation prospects of cryptocurrencies, but the schemes themselves have no real connection to the tech. Virtual currency here is simply a marketing gimmick. Typical charges include fraud, illegal fundraising, or running pyramid schemes. In these scams, virtual currency is just window dressing.

Importantly, virtual currency itself is not the culprit. The blockchain technology behind it holds significant promise for data authentication, cross-border payments, and more. Crypto is both a product of technological innovation and a legal-financial intersection—criminals merely exploit it as a scapegoat for unlawful activity.

In my experience, many in the Web3 community are committed to upholding the reputation of virtual assets and are striving to build legitimate businesses. Regardless of the type, the law judges crypto crimes on the harm done by the conduct itself—not the technology or tools involved.

4. Risk Avoidance Guide

For everyday traders, compliance should always be your bottom line—even as you chase returns. Treat attorney Pang Meimei’s practical advice as your “protective shield”:

Use regulated platforms and legal trading channels. Avoid private deals, unlicensed underground trading venues, and group-based trading;

Keep trades small and individual. Understand your country’s regulatory stance—China, for instance, allows “personal play,” but large-scale or commercial trading (like OTC or brokerage services) can be deemed illegal business. Avoid frequent or large transactions that could be viewed as for-profit. I strongly suggest every trader study the Foreign Exchange Control Regulations;

Keep complete records of transfers and communications to demonstrate your transactions are legal and personal in nature. In the crypto space, it’s wise to keep a low profile—don’t publicly promote crypto investments, recruit others, or organize trading events, no matter your investing acumen;

If you plan to invest large sums or launch a crypto business, consult a qualified attorney beforehand to assess legality and risk—compliance trumps profit. Clarify regulatory boundaries before launching any innovative venture, or what you see as a business model may look like a crime to the courts.

While mainland China currently enforces tight restrictions on virtual currency, Hong Kong’s pilot projects suggest potential for the future. The rise of Web3 calls for proactive legal foresight. I look forward to the day when Web3 professionals and Web3 attorneys can finally remove the “veil” from virtual currency together!

Disclaimer:

- This article is reproduced from [TechFlow]. Copyright remains with the original author [Attorney Pang Meimei]. For any concerns about republication, please contact the Gate Learn team, who will address your inquiry in accordance with applicable procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions of this article are translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless explicitly referencing Gate, translated articles may not be reproduced, distributed, or plagiarized.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?