Burn half of $HYPE? A radical proposal sparks a heated debate on Hyperliquid’s valuation

Recently, as Perp DEXs have surged in popularity, a rapid influx of new projects has emerged, challenging Hyperliquid’s dominance in the space.

While attention has been fixed on innovation from new entrants, the price trajectory of $HYPE—the flagship token—has largely gone unnoticed. Yet the most direct factor influencing token price is $HYPE’s supply.

Two forces drive supply: ongoing buybacks, which continuously absorb circulating tokens to reduce available liquidity—akin to draining a pool—and structural changes to overall supply mechanisms, effectively shutting off the faucet.

A close look at $HYPE’s current supply model reveals key concerns:

The circulating supply is roughly 339 million tokens, with a market capitalization near $15.4 billion; meanwhile, the total supply is nearly 1 billion tokens, giving a fully diluted valuation (FDV) of $46 billion.

This nearly threefold gap between market cap and FDV stems mainly from two sources: 421 million tokens earmarked for Future Emissions and Community Rewards (FECR), and 31.26 million tokens held in the Aid Fund (AF).

The Aid Fund is Hyperliquid’s account for buying back HYPE using protocol revenues. Tokens are bought daily but not burned—just held. The issue: investors see a $46 billion FDV and perceive an overstated valuation, regardless of the smaller circulating supply.

Against this backdrop, Jon Charbonneau (DBA Asset Management, a major HYPE holder) and independent researcher Hasu published an unofficial proposal regarding $HYPE on September 22—one that’s notably bold. The short version:

Destroy 45% of $HYPE’s total supply to bring FDV in line with circulating value.

The proposal instantly sparked intense debate, with the post garnering 410,000 views at the time of reporting.

Why the uproar? If implemented, burning 45% of HYPE’s supply would nearly double the value represented by each token. A significantly lower FDV could entice previously hesitant investors off the sidelines.

We’ve summarized the key points from the original proposal below.

Reducing FDV: Making HYPE Less Expensive

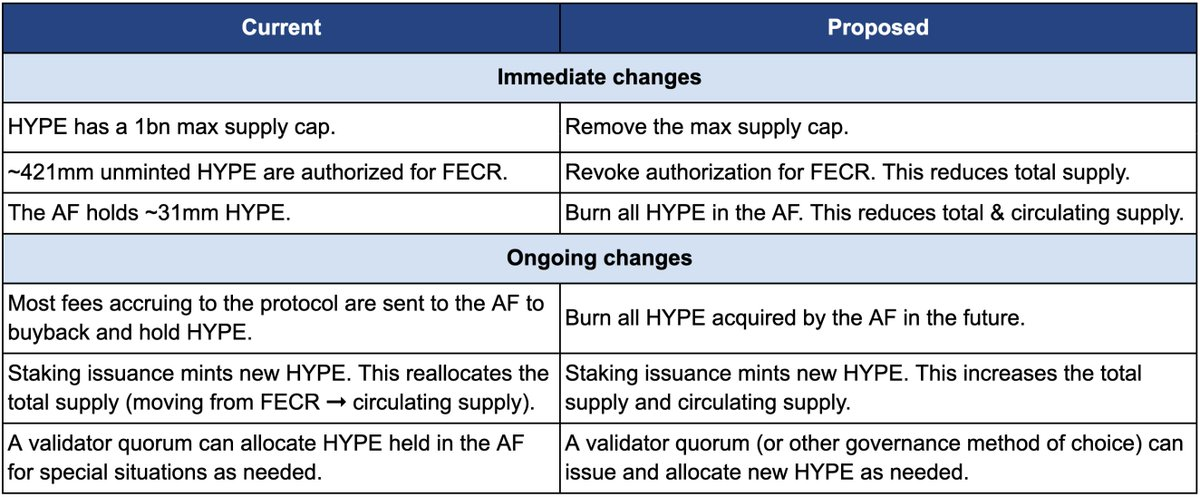

Jon and Hasu’s proposal sounds straightforward—burn 45% of the supply—but actual execution is more complex.

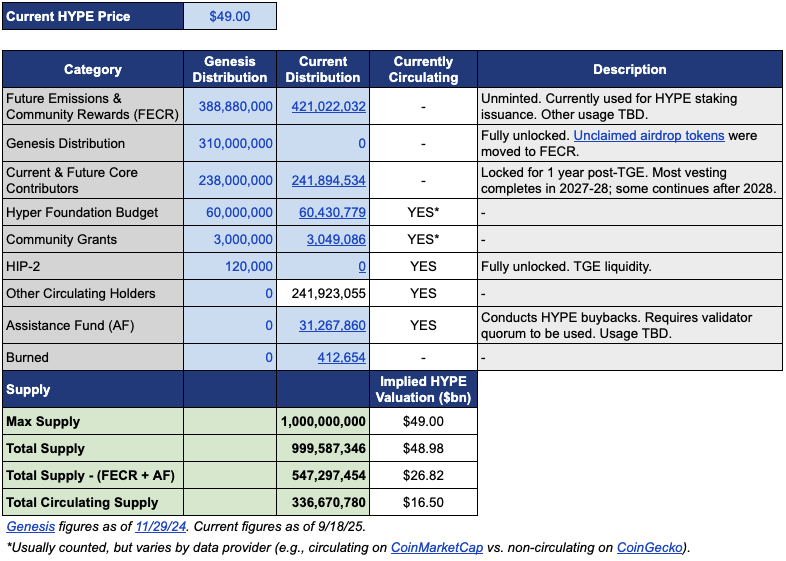

Understanding the proposal requires clarity on HYPE’s supply structure. Per Jon’s data, at a price of $49 (the price when proposed), HYPE has a total supply of 1 billion tokens, with only 337 million in circulation, equating to a $16.5 billion market cap.

So where are the remaining 660 million tokens?

The majority breaks down as 421 million allocated to Future Emissions and Community Rewards (FECR)—a vast reserve with no clear timeline or usage plan—and 31.26 million held by the Aid Fund (AF), which accumulates HYPE daily but does not sell.

The proposal lays out three core steps for burning:

First, revoke authorization for the 421 million FECR tokens. These were intended for future staking rewards and community incentives, but with no set issuance schedule, Jon likens their looming presence to a sword of Damocles over the market. He recommends revoking the authorization and, if needed, reissuing via governance vote.

Second, burn the 31.26 million HYPE held by the Aid Fund (AF), and promptly burn all future HYPE purchased by the AF. Currently, the AF uses protocol income—primarily 99% of trading fees—to buy back roughly $1 million in HYPE daily. Under Jon’s plan, these tokens would be immediately destroyed rather than held.

Third, eliminate the 1 billion token supply cap. This may seem counterintuitive when discussing supply reduction, but Jon clarifies: fixed caps are an outdated vestige from Bitcoin’s 21 million model and are rarely meaningful for most projects. Removing the cap enables future token issuance—such as staking rewards—to be governed and allocated transparently, rather than drawn from pre-reserved pools.

The comparative table below vividly shows “before” and “after” scenarios for the proposal.

Why such an aggressive approach? Jon and Hasu argue that HYPE’s token supply design is primarily an accounting issue—not an economic one.

The problem stems from calculation methodologies at major platforms like CoinMarketCap.

Burned tokens, FECR reserves, and AF holdings are handled differently by each platform when reporting FDV, total supply, and circulating supply. For instance, CoinMarketCap uses the fixed 1 billion supply for FDV calculations regardless of actual burns.

Consequently, no amount of buybacks or burns reduces the displayed FDV.

As the table shows, the proposal would remove both the FECR (421 million) and AF (31 million) tranches, while shifting away from a hard 1 billion cap to a governance-based, demand-driven issuance model.

Jon writes: “Many investors—including some of the largest, most sophisticated funds—look only at headline FDV.” With $46 billion FDV, HYPE appears pricier than Ethereum, deterring buyers.

Still, like most proposals, interests factor in. Jon openly states that his DBA fund holds a material HYPE position, and he personally owns HYPE; he would vote affirmatively if given the chance.

The proposal emphasizes these changes will not impact existing holders’ relative shares, Hyperliquid’s project funding capacity, or the governance model. In Jon’s words,

“This just makes the accounting more transparent.”

When “Community Allocations” Become the Industry’s Unspoken Rule

Will the community embrace this proposal? The comment section on the original thread is already intense.

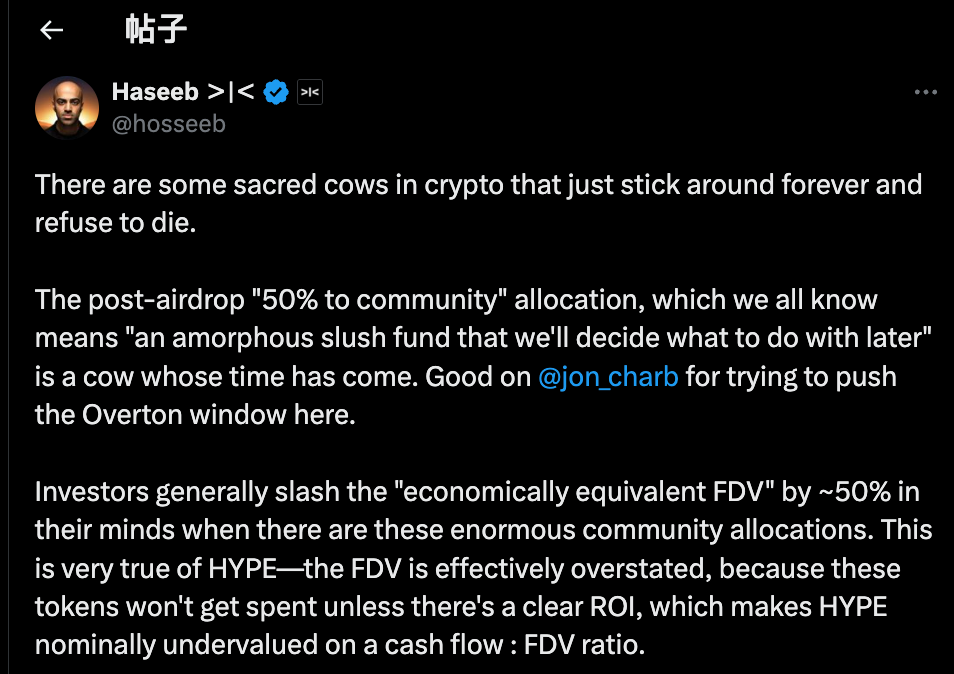

Dragonfly Capital’s partner, Haseeb Qureshi, contextualized the proposal within a broader crypto industry trend:

“There are ‘sacred cows’ in crypto—practices that persist but should be put to rest.”

This refers to the industry’s de facto rule: after token launches, teams routinely reserve 40–50% of supply for the “community.” It sounds decentralized and Web3, but often functions as a performance.

During the 2021 bull market, projects competed to appear the most “decentralized”—tokenomics would flaunt 50%, 60%, even 70% for community, with larger percentages signaling greater political correctness.

But how are these reserves actually used? No one truly knows.

In practice, some project teams treat these allocations as flexible reserves—used whenever and however they wish, all under the banner of “community benefit.”

The market is not naïve.

Haseeb revealed a well-known industry secret: professional investors automatically discount “community reserves” by 50% when valuing projects.

So, a $50 billion FDV project with a 50% community allocation is seen as $25 billion in value unless clear ROI is defined; otherwise, such tokens are mere theoretical promises.

This is HYPE’s exact challenge. Of its $49 billion FDV, over 40% sits in the future emissions and community rewards reserve. Investors see these numbers and step away.

It’s not that HYPE’s fundamentals are poor; the problem is inflated headline figures. Haseeb suggests Jon’s proposal is paving the way for open discussion about radical supply changes—shifting industry norms around “community reserves.”

Supporters’ views are clear:

If tokens are to be used, subject them to governance—clarify rationale, issuance volume, and expected returns. Demand transparency and accountability, not blind trust in a black box.

The radical nature of the proposal has also drawn dissent, which can be grouped into three main arguments:

First, some HYPE is needed for risk reserves.

From a risk management perspective, the 31 million tokens in the AF are not just inventory—they’re emergency contingency funds for regulatory fines or hacks. Burning all reserves would eliminate any safety cushion for crises.

Second, HYPE already employs robust technical burn mechanisms.

Hyperliquid supports three organic burn paths: spot trading fee burns, HyperEVM gas fee burns, and auction fee burns.

These mechanisms naturally adjust supply based on platform usage—making artificial intervention potentially disruptive. Dynamic, usage-based burns are healthier than a large one-off reduction.

Third, a large-scale burn could undermine incentives.

Future emissions are Hyperliquid’s key lever for growth, rewarding users and contributors. Burning them could stunt platform expansion. Large stakers would be locked in, and without new rewards, staking incentives could disappear.

Who Does the Token Serve?

At face value, this is a technical debate about burning tokens. Digging deeper, it’s fundamentally about conflicting interests.

Jon and Haseeb argue that institutional investors are the main drivers of new capital.

These funds manage billions, and their purchases truly move prices. However, when faced with a $49 billion FDV, institutions are deterred. Adjusting this figure is essential for boosting HYPE’s institutional appeal.

The community holds a different view, seeing everyday retail traders as the true foundation. Hyperliquid’s success comes not from venture capital, but from the 94,000 airdrop participants who underpin the ecosystem. Tweaking economic models solely for institutions is seen as losing sight of core values.

This conflict isn’t new.

Historically, almost every successful DeFi project has faced similar crossroads. Uniswap’s token launch saw heated debates between the community and investors over treasury control.

The core question: Are blockchain projects built for institutional capital or for grassroots crypto users?

This proposal caters to institutions—the logic being, “the largest funds focus on FDV.” To bring in big money, the terms must be set to their preference.

Jon, as a proposer, is himself an institutional investor whose fund holds a substantial HYPE position. Should the proposal pass, large holders like him stand to benefit most. Token supply would shrink, price could climb, and portfolio values increase.

Add in Arthur Hayes recently selling $800,000 in HYPE—joking about buying a Ferrari—and the timing becomes conspicuous. Early backers are cashing out, while a new supply burn could push prices higher. Who, ultimately, stands to gain?

As of press time, Hyperliquid has yet to make an official statement. Regardless of the outcome, the debate exposes uncomfortable realities:

Profit drives the conversation. Decentralization may never have truly mattered—it’s just a façade.

Disclaimer:

- This article is republished from [TechFlow], and all copyrights remain with the original author [David, Deep Tide TechFlow]. If you have concerns about republication, please contact the Gate Learn team for prompt resolution.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions have been translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless referring specifically to Gate, reproduction, distribution, or plagiarism of translated content is strictly prohibited.

Related Articles

In-depth Explanation of Yala: Building a Modular DeFi Yield Aggregator with $YU Stablecoin as a Medium

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Dive into Hyperliquid

What is Stablecoin?

Arweave: Capturing Market Opportunity with AO Computer